Basic QC Practices

Leading Laboratories Lag Behind in QC Practices

A new survey of 21 Large Academic Medical Centers in the USA has revealed some sobering facts. We assume that QC processes have evolved from the antique practices of the 1950s and 1960s, particularly since the introduction of "Westgard Rules" in 1981 and other evidence-based optimization techniques in subsequent decades. The reality appears to be the opposite. QC practices may be regressing, not evolving.

Leading Laboratories? They Lag Behind in QC Practices

Sten Westgard, MS

July 2018

The American Journal of Clinical Pathology just published a major wake-up call to US laboratories:

The American Journal of Clinical Pathology just published a major wake-up call to US laboratories:

Quality Control Practices for Chemistry and Immunochemistry in a cohort of 21 Large Academic Medical Center, Rosenbaum MW, Flood JG, Melanson SEF et a. Am J Clin Pathol 2018; 150:96-104.

The authors begin, "[T]o our knowledge, no national pathology/laboratory professional organization has issued detailed guidance statements regarding QC programs. Logically, one may assume that similar laboratories performing the same tests on comparable types of patients would have similar approaches to QC with minor variations due to differing volumes, instruments, and local practices. We surveyed 21 leading academic medical centers regarding their QC approaches to assess similarities and differences in QC practice across different organizations."

What's fortuitous is the timing, because just last year, in 2017, Westgard QC conducted a global survey of QC practices, drawing results from over 900 labs from more than 100 countries. We even summarized the results of just the US laboratories. So we can provide a more robust answer with a broader scope, and at the same time, make a useful comparison between the Leading Academic Centers of the US, and other US labs, and the world.

Leading Labs Lag in Control Rule Implementation

"Most hospitals used a QC rule of 2 SD (n=16, 76%) two (10%) used variable rules (based on the test) between 2 and 3 SD, and one (5%) used a cutoff of 3 SD.... Two (10%) hospitals used derivations of the Westgard rules depending on the assay. For IM [immunochemistry], 17 (81%) hospitals chose a 2-SD rule, one (5%) chose 3 SD, and three (14%) chose some permutation of the Westgard rules."

In the Westgard Global QC Survey, a little over half of labs (55%) reported using 2 SD control rules. In the US, labs are similar (55%).

The global survey also showed that nearly three-quarters of labs (73%) worldwide use "Westgard Rules". In the US, labs are similar (72.7%).

So the "leading labs" are using more antique QC practices and using dramatically fewer Westgard rules, compared not only to their US peers but to their global peers.

Leading Labs Lag in QC interpretation

"When a QC was out of control, all but one hospital elected to repeat the control and accept results if the repeat came back into control (n=20, 95%), although some had some minor variations (such as rejecting a run outright if a control was out by > 4 SD;.... One (5%) institution rejected runs if two controls were out 2 SD or if one was out 3 SD. Another institution (5%) repeated QC if one of the two levels was out 2 SD from target value but accepted the run if only one of three QC levels was out. This institution also rejected outright if the following rules were broken: 1-2.5s. 2-2s, 2/3-2s, or R-4s. Only laboratory E made no provisions for repeating control(s); if one level exceeded 3 SD or two controls exceeded 2 SD, the run was rejected as being out of control."

Oh, dear. There are so many misinterpretations of control rules here it's hard to unpack all the problems. Of course since most labs were implementing antique QC to begin with, it's not surprising they have difficulty trying to implement and interpret more modern control rules. But you see multiple bad habits: repeating controls (the "do-over" response), allowing one level to be out so long as the other levels are in (the "a little bit pregnant" response),

Globally, 78.4% of labs repeat the control after a single outlier. Within the US, 72.5% of labs repeat that control.

So leading labs have a higher rate of repeated controls.

Leading Labs Lag in use of advanced moving averages (patient-data QC)

"Although most of the surveyed hospitals do not currently use moving averages (n=19, 90%), four (19%) are hoping to implement moving averages in the near future....One (5%) institution runs moving averages in the background but does not use them for clinical metrics. Only one (5%) uses moving averages for clinical use and then only for a small number of assays. One of the institutions that did not use moving averages reported that it had previously implemented them but had not found them to be useful."

This is in stark contrast to all the literature and conference sessions devoted to the topic of moving averages. Moving Averages, Average of Normals, Patient Data QC, whatever you call it, the technique is perennially hailed as the most advanced QC, the next generation of QC, the solution to our current QC problems. Yet the major academic centers essentially do not use it. There is a failure of informatics here, a failure of leadership, and a glaring gap between the theoretical benefit and the practical challenges of implementation. Clearly, there is still a need for better informatics to enable these QC techniques - as well as a stronger commitment by labs to comprehend, embrace and utilize them.

Globally, we found that 11% of labs use Average of Normals. Within the US, it's even fewer labs, only 9.2%.

Leading Labs Lag in Evidence-Based QC Frequency

"There were no apparent trends between QC frequency and manufacturer, and variation existed between laboratories using similar instruments. Therefore, it seems unlikely that platform choice alone would affect QC practices to a significant extent. A factor that supports this is that, in most institutions that used instruments from multiple manufacturers, QC rules did not vary notably between the instruments....There was dramatic (ie, 12-fold) variation in QC frequency, ranging from once daily to every 2 hours. This was surprising because, although QC frequency may vary based on the device used, reagent stability, and test volume, the clinical risk associated with result errors should be more or less similar among the cohort, especially for CHEM/IM testing."

It may not be a reasonable assumption to conclude that platform choice should not affect QC practices. What we have clearly seen in this cohort is that QC choices are not being evidence-based or data-driven, they are motivated by old habits and simple heuristics. QC rules and QC frequency are being applied in arbitrary ways, sometimes in a one-size-fits-all fashion, without regard for instrument or method performance. If we knew the real performance (CV, bias) of these labs, we could apply a more optimized approach to QC rules and QC frequency.

QC Frequency, in the last few years, has evolved from an arbitrary heuristic (once a day, once a shift), into something that can be determined by performance. We have the tools now to know exactly how many patients specimens can be run in between controls without raising the risk to patients. This is an advanced technique that, evidently, none of the leading academic medical centers have adopted.

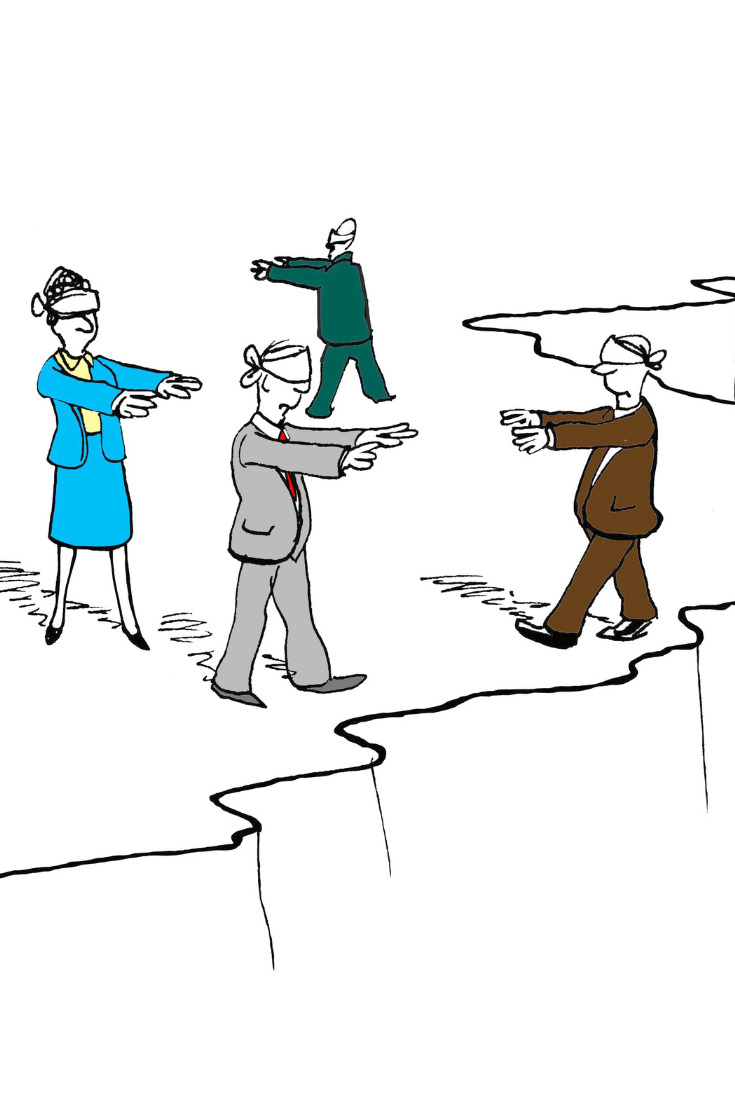

Conclusion: When it comes to Quality, Leading Labs are not Leading

It is too painful right now to admit: sometimes the US is no longer the leader in best practices in the world. This is true for laboratory quality. Labs seeking guidance for best QC practices would do well to look elsewhere than "leading academic medical centers". And those centers would be well advised to renew their commitment to quality, brush up on their QC skills, and reclaim their leadership.

Everyone share some of the blame for this lagging behavior. Manufacturers, more focused on the revenue than the performance, enable their customers to adopt any QC practices that reduces the number of complaints and phone calls. Control vendors, more focused on revenue than the performance, enable their customers to repeat controls, run more controls, and run still more controls more often, without providing them useful guidance on the right rules, the right number of controls, the right frequency of controls. Even the Westgards bear some of this fault, because we provide many tools, but we too often don't provide the examples and the guidance of how to use the tools in the real world.

Once when I was visiting a leading academic medical center, one of the staff put it to me like this: you're expected to teach 100% of the time, research 100% of the time, and run the lab 100% of the time. The additional pressures that come with working in a premiere medical center laboratory often mean that some of the "basic" core tasks are not given the attention they deserve. So much needs to be done, it's easy to overlook the QC and just maintain the status quo, even if that is a fifty-year-old tradition long outdated.

The authors conclude: "We believe that most academic medical center chemistry laboratories... may benefit from a standardized approach to QC for routine chemistry/immunochemistry testing and that can withstand rigorous statistical validation. The survey results suggest an opportunity for laboratory professional organizations to convene a consensus panel to determine a best practice approach (or approaches) to QC in the chemistry laboratory."

We wholeheartedly agree. Although if those labs look around, they may find there are plenty of useful best practice recommendations available right now.