Basic QC Practices

Great Global QC Survey of Hematology Practices

In 2017, we conducted a QC Survey all over the world. But we primarily focused on the chemistry practices. What about hematology practices? We have just enough responses to help us paint a picture of the state of hematology QC.

The Great Global QC Survey: How Hematology Runs QC

February 2018

Sten Westgard, MS

After looking at the breakdown of the Great Global QC Survey results between US and outside the US, as well as veterinary laboratories, we decided to go one step further. While the vast majority of the responses were focused on how QC is performed for the biochemistry methods, more than 100 responses detailed what was going on in the hematology section. And, you might be surprised, there are some significant differences.

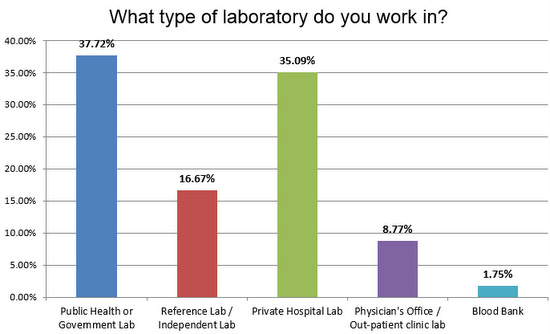

Unlike the US, where mostly private hospital laboratories responded to the survey, the most common type of labs responding to this survey were public laboratories. That makes sense when we consider that many healthcare systems in the region are socialized and run as public institutions.

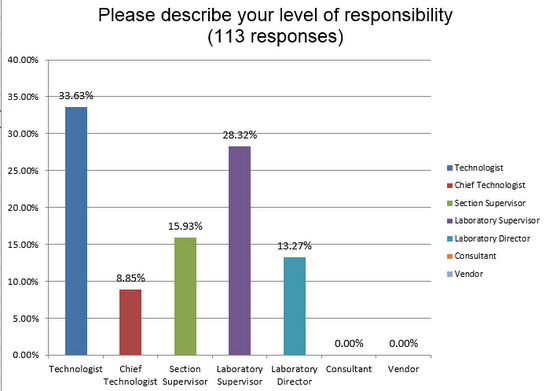

We received responses from people right at the bench level, technologists and their immediate supervisors who really have their hands on the instruments.

Public, private, or reference lab: who responded?

There was a good split of public and private laboratories responding to the survey, and a healthy number of reference laboratories.

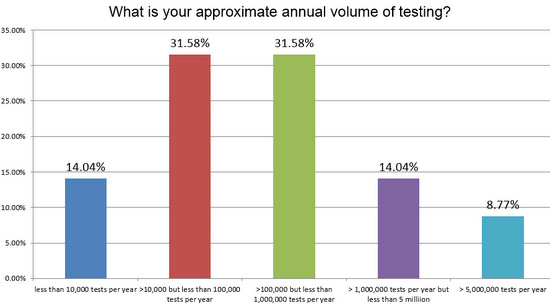

Now, what was the volume of testing in these responding laboratories?

There's a pretty even split between high and low volume laboratories responding to the survey, but there are also a fair representation of the high volume labs, those running more than 5MM tests a year.

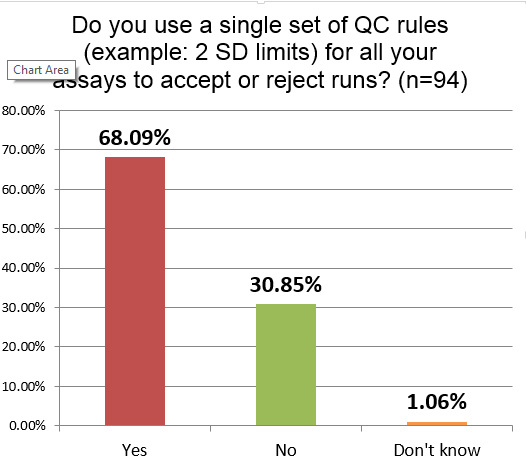

Let's get right to the QC practices of all of these laboratories:

More than two-thirds of hematology sections are using just one set of single control limits (probably 2 SD) on all their tests. While a majority of labs in chemistry and other sectinos use this antiquated approach, these results show that hematology laboratories are even more uniform in their policies. If the 2 SD is being set using the actual SD of the laboratory, this approach will result in a high number of unnecessary outliers and false rejections.

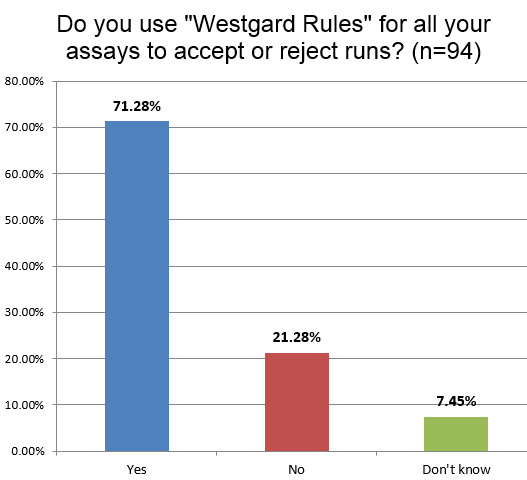

About the same percentage of labs in hematology (71%) use "Westgard Rules" as the chemistry section (73% globally). This is interesting since one of the frequent questions we get from hematology lab techs is, "Do 'Westgard Rules' apply in hematology?" (The answer is mostly YES). We also hear that many manufacturers try to dissuade their customers from using "Westgard Rules" in a transparent attempt to reduce the number of outliers and technical support calls. As we always say, the rules depend on the Sigma-metric. If it turns out you have hematology methods performing at Six Sigma, you don't need all the "Westgard Rules", single 3 SD limits will easily suffice. So there may indeed be cases where hematology instruments are using too many "Westgard Rules." but that will need to be determined by each laboratory.

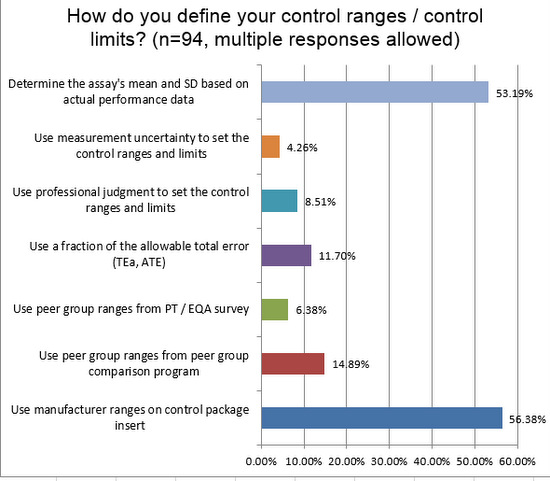

More than half of laboratories use their own mean and standard deviation when setting up their control limits, ranges, and charts. This is encouraging. Nevertheless, you can see a that more than half also use manufacturer ranges in their charts. This is a practice more common in hematology than in chemistry and immunoassay. The problem is the manufacturer ranges are typically too wide, sometimes more than twice as wide as the should be if they reflected the actual SD of the laboratory.

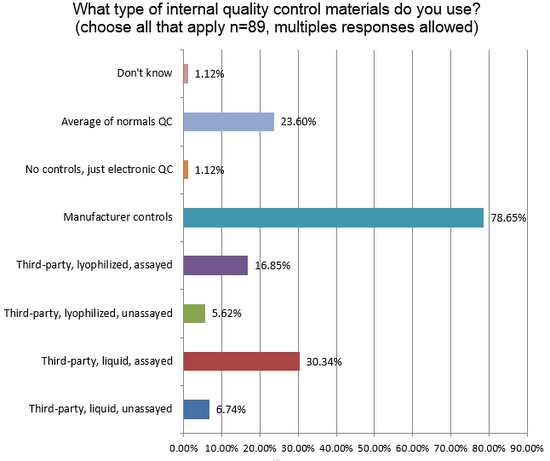

Nearly 80% of laboratories are using manufacturer controls, significantly higher than what is seen in chemistry (64%), despite the strong recommendation from ISO 15189 and other guidelines to use independent, third-party controls. The second-most popular type of control in use around the world is liquid, assayed third-party control. Other significant findings here include (1) twice as many labs in hematology use some type of patient data for QC (Bull's Algorithm, for example) than we see in the chemistry side; and (2) almost no laboratories are using just electronic QC. In the US, where POC devices are proliferating, the electronic QC is often the only practical method of controlling quality. Outside the US, POC usage is not as high, and so fewer labs use electronic QC.

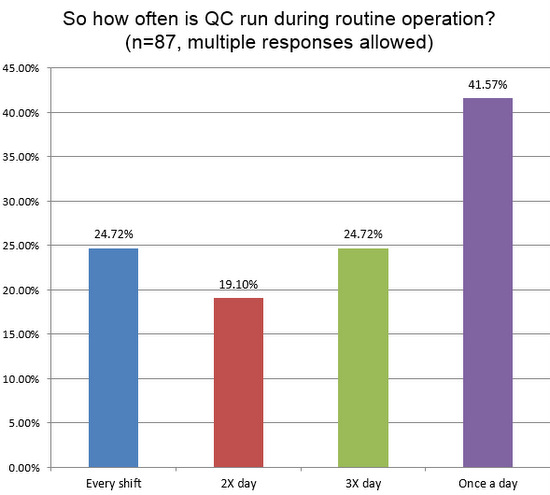

A quarter of labs are reporting they run controls three times per day, or once per shift. Less than a majority of labs are running QC only once a day. So hematology sections continue to run QC more frequently than their counterparts in chemistry.

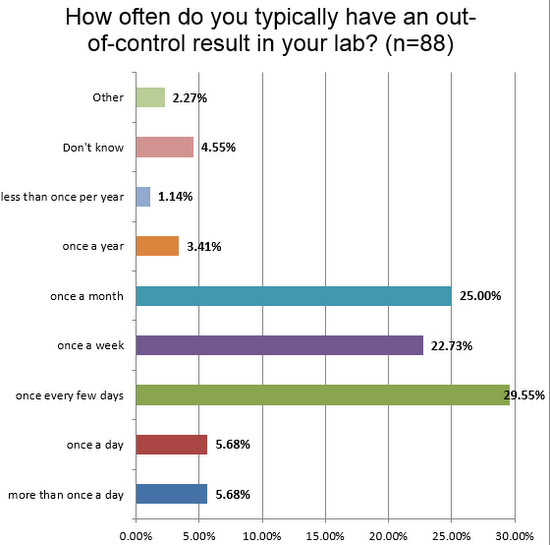

About 1 in 10 labs see out-of-control flags at least once a day. This is a marked difference from the chemistry side, where it is as high as 1 in 3 labs. Given that we've already seen too many labs are using manufacturer limits, which are too wide, it raises a question: are there even more errors occurring that are being missed? Or are there a lot of false rejections confusing the issue. Irregardless, the net effect of so many alarms is a form of alert fatigue: labs see so many errors they stop treating each one as serious.

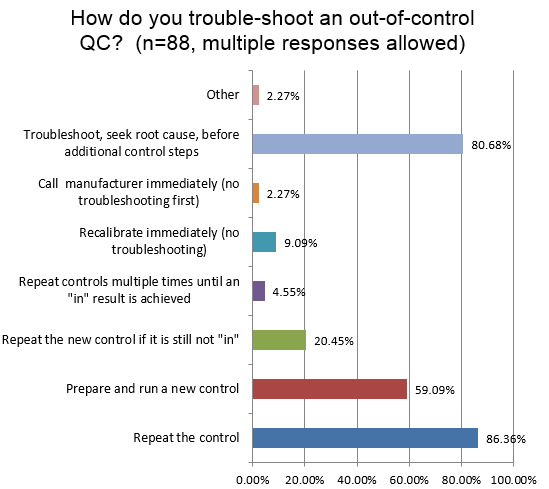

An extremely high percentage of hematology technicians simply repeat the control when there is an out-of-control signal. And a majority of labs will also run a new control, after a single repeat fails. One in five labs will keep repeating the control again. And nearly one in twenty labs will simply repeat the controls until it finally falls "in." Now, the good news is that 80% of labs still report that they will do the correct thing: which is to not blindly repeat a control, but instead perform real trouble-shooting and seek the root cause for the error. Compared to what we see in the chemistry answers, there are more repeats being performed in hematology. We call this, "Gambler QC."

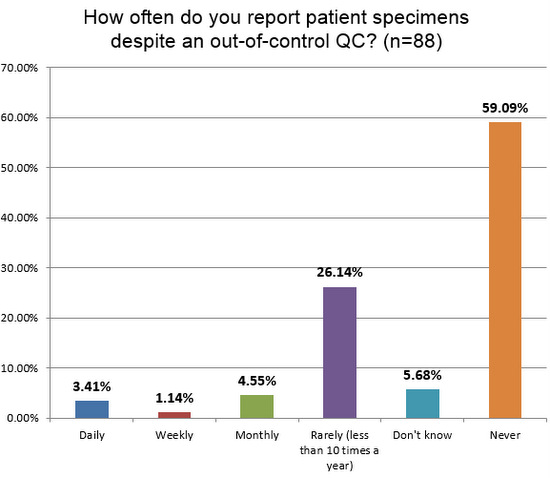

What happens when all the wrong ranges, wrong limits, wrong rules, wrong repeats and more corrupt the practice of QC? It's not good. Nearly 1 in 10 labs admit to releasing patient results every month (or more frequently), even when they have an out-of-control result. This is the same rate found on the chemistry side. When QC is corrupted by poor practices, we're in danger of compromising patient results.

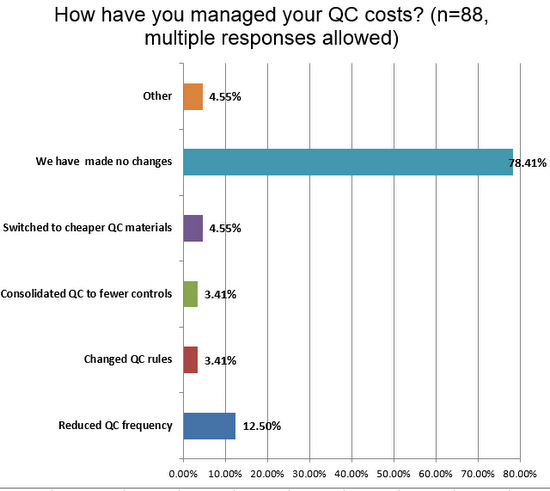

Finally, there is the question of resources and finances. More than what we've seen on the chemistry side, a vast majority of hematology sections have made no changes to their QC to manage costs. However distressing this is, it does mean there may be "low hanging fruit" for labs seeking cost savings and efficiency gains. Considering a change to consolidated or cheaper controls may be a way to reduce laboratory costs without compromising quality, when paired with the use of the right tools. And if the assays in the laboratory are of high quality, even more savings can be realized.

Conclusion

There are some limitations about these findings, particularly since we had a small number of responses focusing on this testing area. But the summary of these answers show a profound separation between the perception of hematology performance and the actual practice of hematology QC. Often hematology methods are considered an area where few analytical problems are encountered. But there are actually signs that hematology QC may still be in worse shape than what is performed on the chemistry side.